Synthisophy

Skinwalkers - Chapter 18

The following are direct quotes from the book Tribe, On Homecoming and Belonging, by Sebastian Junger, May 2016, except for statements in italic added.

The ultimate act of disaffiliation isn’t littering or fraud, of course, but violence against your own people. When the Navajo Nation—the Diné, in their language—were rounded up and confined to a reservation in the 1860s, a terrifying phenomenon became more prominent in their culture. The warrior skills that had protected the Diné for thousands of years were no longer relevant in this dismal new era, and people worried that those same skills would now be turned inward, against society. That strengthened their belief in what were known as skinwalkers, or yee naaldlooshii.

Skinwalkers were almost always male and wore the pelt of a sacred animal so that they could subvert that animal’s powers to kill people in the community. They could travel impossibly fast across the desert and their eyes glowed like coals and they could supposedly paralyze you with a single look. They were thought to attack remote homesteads at night and kill people and sometimes eat their bodies. People were still scared of skinwalkers when I lived on the Navajo Reservation in 1983, and frankly, by the time I left, I was too.

Virtually every culture in the world has its version of the skinwalker myth. In Europe, for example, they are called werewolves (literally “man-wolf” in Old English). The myth addresses a fundamental fear in human society: that you can defend against external enemies but still remain vulnerable to one lone madman in your midst. Anglo-American culture doesn’t recognize the skinwalker threat but has its own version. Starting in the early 1980s, the frequency of rampage shootings in the United States began to rise more and more rapidly until it doubled around 2006. Rampages are usually defined as attacks where people are randomly targeted and four or more are killed in one place, usually shot to death by a lone gunman. As such, those crimes conform almost exactly to the kind of threat that the Navajo seemed most to fear on the reservation: murder and mayhem committed by an individual who has rejected all social bonds and attacks people at their most vulnerable and unprepared. For modern society, that would mean not in their log hogans but in movie theaters, schools, shopping malls, places of worship, or simply walking down the street.

Here is a list of skinwalkers, and their shooting rampages in the USA over the last 30 years. Note that from 1988 to 1997 there were 6; from 1998 to 2007 there were 9; from 2008 to 2017 there were 24. Why does it appear that over the last 10 years our society is generating a sharp increase in skinwalkers, individuals committing murder and mayhem who have rejected all social bonds and attack people at their most vulnerable and unprepared? Perhaps it is because, as Sebastion Junger stated, this “shows how completely detribalized this country has become.” Our neurological genetic predisposition, the warrior ethos, all for 1 and 1 for all, is no longer relevant in modern life. As individuals in society it appears we are now very far from our evolutionary roots.

In 2013, areport from the Congressional Research Service, known as Congress's think tank, described mass shootings as those in which shooters "select victims somewhat indiscriminately" and kill four or more people.

From: http://timelines.latimes.com/deadliest-shooting-rampages/

Mass shootings over last 30 years until October 1, 2017. And recent news from October 2 to December 31, 2017.

November 14, 2017: Rampaging through a small Northern California town, a gunman took aim on Tuesday at people at an elementary school and several other locations, killing at least four and wounding at least 10 before he was fatally shot by police, the local sheriff’s office said.

November 5, 2017: Devin Patrick Kelley carried out the deadliest mass shooting in Texas history on Sunday, killing 25 people and an unborn child at First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, near San Antonio.

October 1, 2017: 58 killed, more than 500 injured: Las Vegas

More than 50 people were killed and at least 500 others injured when a gunman opened fire at a country music festival near the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip, authorities said. Police said the suspect, 64-year-old Stephen Paddock, a resident of Mesquite, Nev., was was found dead after a SWAT team burst into the hotel room from which he was firing at the crowd.

Jan. 6, 2017: 5 killed, 6 injured: Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

After taking a flight to Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport in Florida, a man retrieves a gun from his luggage in baggage claim, loads it and opens fire, killing five people near a baggage carousel and wounding six others. Dozens more are injured in the ensuing panic. Esteban Santiago, a 26-year-old Iraq war veteran from Anchorage, Alaska, has pleaded not guilty to 22 federal charges.

May 28, 2017: 8 killed, Lincoln County, Miss. A Mississippi man went on a shooting spree overnight, killing a sheriff's deputy and seven other people in three separate locations in rural Lincoln County before the suspect was taken into custody by police, authorities said on Sunday.

Sept. 23, 2016: 5 killed: Burlington, Wash.

A gunman enters the cosmetics area of a Macy’s store near Seattle and fatally shoots an employee and four shoppers at close range. Authorities say Arcan Cetin, a 20-year-old fast-food worker, used a semi-automatic Ruger .22 rifle that he stole from his stepfather’s closet.

June 12, 2016: 49 killed, 58 injured in Orlando nightclub shooting

The United States suffered one of the worst mass shootings in its modern history when 49 people were killed and 58 injured in Orlando, Fla., after a gunman stormed into a packed gay nightclub. The gunman was killed by a SWAT team after taking hostages at Pulse, a popular gay club. He was preliminarily identified as 29-year-old Omar Mateen.

Dec. 2, 2015: 14 killed, 22 injured: San Bernardino, Calif.

Two assailants killed 14 people and wounded 22 others in a shooting at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino. The two attackers, who were married, were killed in a gun battle with police. They were U.S.-born Syed Rizwan Farook and Pakistan national Tashfeen Malik, and had an arsenal of ammunition and pipe bombs in their Redlands home.

Nov. 29, 2015: 3 killed, 9 injured: Colorado Springs, Colo.

A gunman entered a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs, Colo., and started firing.

Police named Robert Lewis Dear as the suspect in the attacks.

Oct. 1, 2015: 9 killed, 9 injured: Roseburg, Ore.

Christopher Sean Harper-Mercer shot and killed eight fellow students and a teacher at Umpqua Community College. Authorities described Harper-Mercer, who recently had moved to Oregon from Southern California, as a “hate-filled” individual with anti-religion and white supremacist leanings who had long struggled with mental health issues.

July 16, 2015: 5 killed, 3 injured: Chattanooga, Tenn. A gunman opened fire on two military centers more than seven miles apart, killing four Marines and a Navy sailor. A man identified by federal authorities as Mohammod Youssuf Abdulazeez, 24, sprayed dozens of bullets at a military recruiting center, then drove to a Navy-Marine training facility and opened fire again before he was killed.

June 18, 2015: 9 killed: Charleston, S.C.

Dylann Storm Roof is charged with nine counts of murder and three counts of attempted murder in an attack that killed nine people at a historic black church in Charleston, S.C. Authorities say Roof, a suspected white supremacist, started firing on a group gathered at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church after first praying with them. He fled authorities before being arrested in North Carolina.

May 23, 2014: 6 killed, 7 injured: Isla Vista, Calif.

Elliot Rodger, 22, meticulously planned his deadly attack on the Isla Vista community for more than a year, spending thousands of dollars in order to arm and train himself to kill as many people as possible, according to a report released by the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office. Rodger killed six people before shooting himself.

April 2, 2014: 3 killed; 16 injured: Ft. Hood, Texas

A gunman at Fort Hood, the scene of a deadly 2009 rampage, kills three people and injures 16 others, according to military officials. The gunman is dead at the scene.

Sept. 16, 2013: 12 killed, 3 injured: Washington, D.C. Aaron Alexis, a Navy contractor and former Navy enlisted man, shoots and kills 12 people and engages police in a running firefight through the sprawling Washington Navy Yard. He is shot and killed by authorities.

June 7, 2013: 5 killed: Santa Monica

John Zawahri, an unemployed 23-year-old, kills five people in an attack that starts at his father’s home and ends at Santa Monica College, where he is fatally shot by police in the school’s library.

Dec. 14, 2012: 27 killed, one injured: Newtown, Conn.

A gunman forces his way into Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. and shoots and kills 20 first graders and six adults. The shooter, Adam Lanza, 20, kills himself at the scene. Lanza also killed his mother at the home they shared, prior to his shooting rampage.

Aug. 5, 2012: 6 killed, 3 injured: Oak Creek, Wis.

Wade Michael Page fatally shoots six people at a Sikh temple before he is shot by a police officer. Page, an Army veteran who was a “psychological operations specialist,” committed suicide after he was wounded. Page was a member of a white supremacist band called End Apathy and his views led federal officials to treat the shooting as an act of domestic terrorism.

July 20, 2012: 12 killed, 58 injured: Aurora, Colo.

James Holmes, 24, is taken into custody in the parking lot outside the Century 16 movie theater after a post-midnight attack in Aurora, Colo. Holmes allegedly entered the theater through an exit door about half an hour into the local premiere of “The Dark Knight Rises.”

April 2, 2012: 7 killed, 3 injured: Oakland

One L. Goh, 43, a former student at a Oikos University, a small Christian college, allegedly opens fire in the middle of a classroom leaving seven people dead and three wounded.

Jan. 8, 2011: 6 killed, 11 injured: Tucson, Ariz.

Jared Lee Loughner, 22, allegedly shoots Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in the head during a meet-and-greet with constituents at a Tucson supermarket. Six people are killed and 11 others wounded.

Nov. 5, 2009: 13 killed, 32 injured: Ft. Hood, Texas

Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, an Army psychiatrist, allegedly shoots and kills 13 people and injures 32 others in a rampage at Ft. Hood, where he is based. Authorities allege that Hasan was exchanging emails with Muslim extremists including American-born radical Anwar Awlaki.

April 3, 2009: 13 killed, 4 injured: Binghamton, N.Y.

Jiverly Voong, 41, shoots and kills 13 people and seriously wounds four others before apparently committing suicide at the American Civic Assn., an immigration services center, in Binghamton, N.Y.

Feb. 14, 2008: 5 killed, 16 injured: Dekalb, Ill.

Steven Kazmierczak, dressed all in black, steps on stage in a lecture hall at Northern Illinois University and opens fire on a geology class. Five students are killed and 16 wounded before Kazmierczak kills himself on the lecture hall stage.

Dec. 5, 2007: 8 killed, 4 injured: Omaha

Robert Hawkins, 19, sprays an Omaha shopping mall with gunfire as holiday shoppers scatter in terror. He kills eight people and wounds four others before taking his own life. Authorities report he left several suicide notes.

April 16, 2007: 32 killed, 17 injured: Blacksburg, Va.

Seung-hui Cho, a 23-year-old Virginia Tech senior, opens fire on campus, killing 32 people in a dorm and an academic building in attacks more than two hours apart. Cho takes his life after the second incident.

Feb. 12, 2007: 5 killed, 4 injured: Salt Lake City

Sulejman Talovic, 18, wearing a trenchcoat and carrying a shotgun, sprays a popular Salt Lake City shopping mall. Witnesses say he displays no emotion while killing five people and wounding four others.

Oct. 2, 2006: 5 killed, 5 injured: Nickel Mines, Pa.

Charles Carl Roberts IV, a milk truck driver armed with a small arsenal, bursts into a one-room schoolhouse and kills five Amish girls. He kills himself as police storm the building.

July 8, 2003: 5 killed, 9 injured: Meridian, Miss.

Doug Williams, 48, a production assemblyman for 19 years at Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Co., goes on a rampage at the defense plant, fatally shooting five and wounding nine before taking his own life with a shotgun.

Dec. 26, 2000: 7 killed: Wakefield, Mass.

Michael McDermott, a 42-year-old software tester shoots and kills seven co-workers at the Internet consulting firm where he is employed. McDermott, who is arrested at the offices of Edgewater Technology Inc., apparently was enraged because his salary was about to be garnished to satisfy tax claims by the Internal Revenue Service. He uses three weapons in his attack.

Sept. 15, 1999: 7 killed, 7 injured: Fort Worth

Larry Gene Ashbrook opens fire inside the crowded chapel of the Wedgwood Baptist Church. Worshipers, thinking at first that it must be a prank, keep singing. But when they realize what is happening, they dive to the floor and scrunch under pews, terrified and silent as the gunfire continues. Seven people are killed before Ashbrook takes his own life.

April 20, 1999: 13 killed, 24 injured: Columbine, Colo.

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, students at Columbine High, open fire at the school, killing a dozen students and a teacher and causing injury to two dozen others before taking their own lives.

March 24, 1998: 5 killed, 10 injured: Jonesboro, Ark.

Middle school students Mitchell Johnson and Andrew Golden pull a fire alarm at their school in a small rural Arkansas community and then open fire on students and teachers using an arsenal they had stashed in the nearby woods. Four students and a teacher who tried shield the children are killed and 10 others are injured. Because of their ages, Mitchell. 13, and Andrew, 11, are sentenced to confinement in a juvenile facility until they turn 21.

Dec. 7, 1993: 6 killed, 19 injured: Garden City, N.Y.

Colin Ferguson shoots and kills six passengers and wounds 19 others on a Long Island Rail Road commuter train before being stopped by other riders. Ferguson is later sentenced to life in prison.

July 1, 1993: 8 killed, 6 injured: San Francisco

Gian Luigi Ferri, 55, kills eight people in an office building in San Francisco’s financial district. His rampage begins in the 34th-floor offices of Pettit & Martin, an international law firm, and ends in a stairwell between the 29th and 30th floors where he encounters police and shoots himself.

May 1, 1992: 4 killed, 10 injured: Olivehurst, Calif.

Eric Houston, a 20-year-old unemployed computer assembler, invades Lindhurst High School and opens fire, killing his former teacher Robert Brens and three students and wounding 10 others.

Oct. 16, 1991: 22 killed, 20 injured: Killeen, Texas

George Jo Hennard, 35, crashes his pickup truck into a Luby’s cafeteria crowded with lunchtime patrons and begins firing indiscriminately with a semiautomatic pistol, killing 22 people. Hennard is later found dead of a gunshot wound in a restaurant restroom.

June 18, 1990: 10 killed, 4 injured: Jacksonville, Fla.

James E. Pough, a 42-year-old day laborer apparently distraught over the repossession of his car, walks into the offices of General Motors Acceptance Corp. and opens fire, killing seven employees and one customer before fatally shooting himself.

Jan. 17, 1989: 5 killed, 29 injured: Stockton, Calif.

Patrick Edward Purdy turns a powerful assault rifle on a crowded school playground, killing five children and wounding 29 more. Purdy, who also killed himself, had been a student at the school from kindergarten through third grade.Police officials described Purdy as a troubled drifter in his mid-20s with a history of relatively minor brushes with the law. The midday attack lasted only minutes.

July 18, 1984: 21 killed, 19 injured: San Ysidro, Calif.

James Oliver Huberty, a 41-year-old out-of-work security guard, kills 21 employees and customers at a McDonald’s restaurant. Huberty is fatally shot by a police sniper perched on the roof of a nearby post office.

Synthisophy

Integrate the Wisdoms of History into Present Culture

Addressing the polarized political climate in the USA

Add Text Here...

.

Fantasyland is a term used to describe one’s perception of reality, one’s neuroreality, when that perception is far from actual reality. The following are quotes from the book; Fantasyland, How America Went Haywire, a 500 Year History, 2017, by Kurt Andersen, some bolded for emphasis, except for statements and additional information with sources added in italic. Page numbers are included.

18

All That Glitters: The Gold-Seekers

During the 1500s too, European fantasies of worldly splendors had just acquired a thrilling new inspiration and focus. In 1492 Columbus had sailed west in search of a shorter route by sea from Europe to Asia that might replace the overland Silk Road trip - an impossible dream then and for four hundred years afterward. Instead of Japan, he got the Bahamas. But he had discovered a New World. It was a blank slate on which fantastic wealth and glory could be imagined from three thousand miles away.

More European explorers quickly followed and would keep coming, many of them pursuing the dream of a Northwest Passage. That was the dream of Captain John Smith at the beginning of the 1600s when he sailed to the New World, funded by English investors. Imagining that the Potomac River led all the way to the Pacific Ocean, Smith got only as far as Bethesda, Maryland. Passage to Asia was also the dream in 1609 of the Englishman Henry Hudson, who got only as far as Albany. A year later English investors who wanted to believe the Arctic-trade-route dream financed Hudson to try again. This time instead of China, he made it to Ontario; when Hudson

19

wanted to keep going west, his crew, not as enraptured by the fantasy, mutinied, Captain Hudson was never seen again. But the Spaniards who followed Columbus, instead of searching in vain for a Northwest Passage to Asia, headed southwest. There they discovered advanced civilizations with cities, the Aztec in Mexico and the Inca in South America. And there too they found the Aztecs' and Incas' gold - which they stole and mined for more than a century, thereby establishing a transatlantic empire.

The English envied the suddenly powerful Spanish - and their New World gold in particular.

If there was so much treasure for the taking in the southern reaches, why not thousands of miles closer, in the north, in the lands closest to England? Thus the quest for gold became a fetish for would-be English colonists as the 1500s turned into the 1600s. It also established a theme we'll encounter again and again: around some plausible bit of reality, Americans leap to concoct wishful (or terrified) fictions they ardently believe to be true.

Chapter 22

Fantasyland

A young Oxford graduate and royal factotum named Richard Hakluyt was among the most excited and influential of England's America enthusiasts during the 1580s and 1590s. He cherry-picked the reports of earlier explorers, many of them second and third hand, to depict a perfectly ripe paradise. All those probes into eastern North America, he wrote in a forty-thousand-word manuscript, “prove infallibly unto us that gold, silver . . . precious stones, and turquoises, and emeralds . . . have been by them found" up and down the coast. The southern part "had in the land gold and silver"; a bit to the north there was also sure to be gold because "the colour of the land doth altogether argue it"; and farther north too "there is mention of silver and gold." At the time, England's population was growing faster than its economy, so Hakluyt proposed shipping off "idle men" to America and "setting them to work in mines of gold."

It was inconvenient that humans already inhabited the northern New World. However, Hakluyt reported that the natives were "people good and of a gentle and amiable nature, which willingly will obey." And North America's population density was less than 5 percent of Britain's, so to the newcomers it appeared essentially empty, a tabula rasa ready to be transformed into some brand of English utopia.

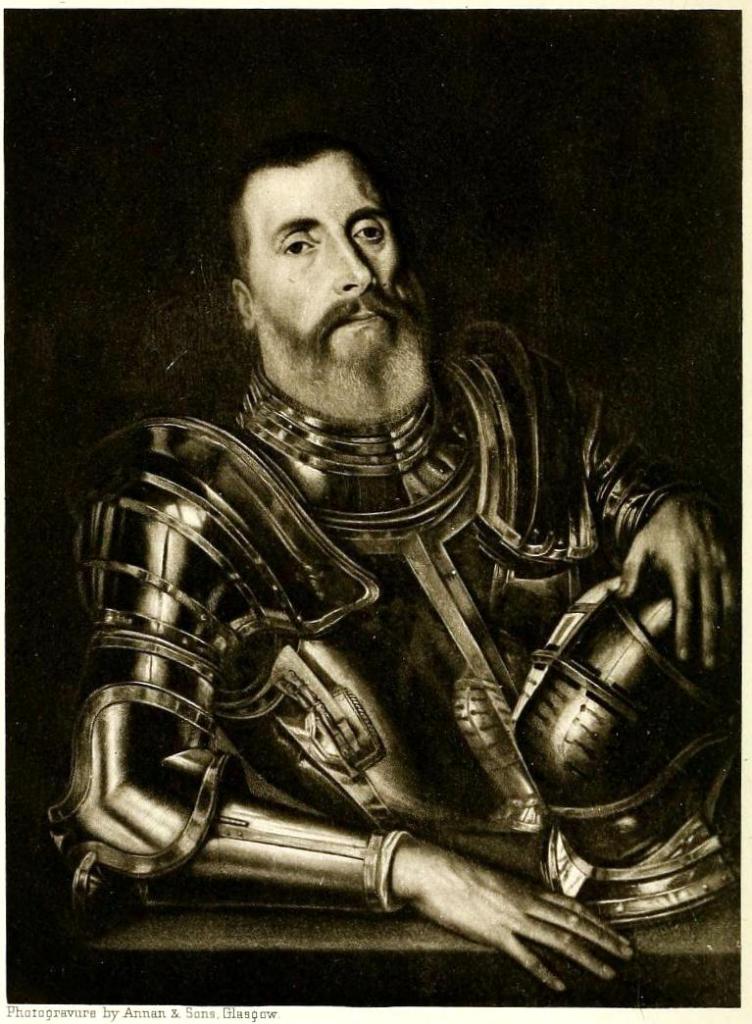

Hakluyt's breathless chronicle of America had been commissioned by the thirty-year-old aristocrat, poet, rake, adventurer, zealous Protestant, and gold-mad New World enthusiast Walter Raleigh:

He was a charming, Iarger-than-life up-and-comer - a stereotypical go-go American before English

20

America even existed. As soon as he'd had Hakluyt write his report on the New World, meant to convince Queen Elizabeth to colonize, Raleigh over the course of just three years became Sir Walter Raleigh; got the royal franchise to exploit and govern the eastern coast of North America; and sent three separate expeditions of Englishmen to get the gold. They found none.

Although Raleigh never visited North America himself he believed that in addition to its gold deposits, his realm might somehow be the biblical Garden of Eden. English clergymen had calculated from the Bible that Eden was at a latitude of thirty-five degrees north - just like Roanoke Island, they said. And there was still more fresh (hearsay) evidence of divine magic in Virginia: a botanist's book, Joyful News of the New Found World, reported that various plants unique to America cured all diseases. A famous English poet published his "Ode to the Virginian Voyage," calling Virginia "Earth's only Paradise" where Britons would “get the pearl and gold" - and plenty of English people imagined that it was literally a new Eden. Alas, no. A large fraction of the first settlers dispatched by Raleigh became sick and died. He dispatched a second expedition of gold-hunters. It also failed, and all those colonists died.

But Sir Walter continued believing the dream of gold. He failed to find the legendary golden city of El Dorado when he sailed to South America in 1595, but that didn't stop him from propagating the fantasy in England. He published a book about it that consisted of secondhand historical anecdotes meant to make the dream seem real. Raleigh helped invent the kind of elaborate pseudoempiricism that in the centuries to come would become a permanent feature of Fantasyland testimonials - about religion, about quack science, about conspiracy, about whatever was being urgently sold.

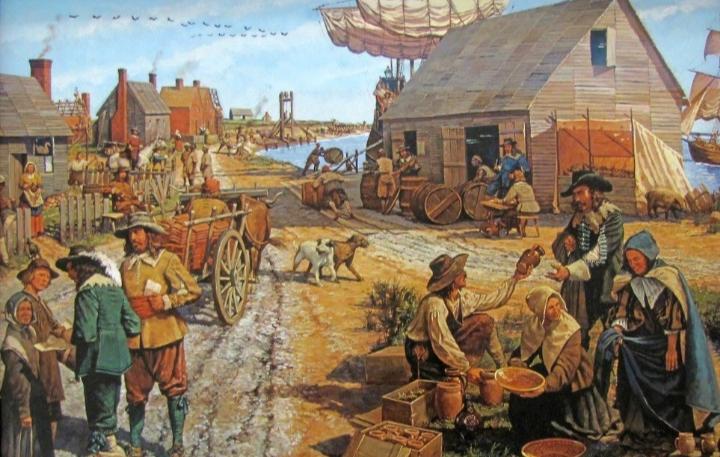

In 1606 the new English king, James, despite Raleigh's colonization disasters, gave a franchise to two new private enterprises, the Virginia Company of London and the Virginia Company of Plymouth, to start colonies. The southern one, under the auspices of London, they named Jamestown after the monarch. Their royal charter was clear about the main mission: "to dig, mine, and search for all Manner of Mines of Gold . . . And to HAVE and enjoy the Gold." As Tocqueville wrote in his history two centuries later, "lt was . . . gold-seekers who were sent to Virginia. No noble thought or conception

21

above gain presided over the foundation of the new settlements." Two- thirds of those first hundred gold-seekers promptly died. But the captain of the expedition returned to England claiming to have found "gold showing mountains."

Hakluyt, a director of the London Company, never managed to get to America but never stopped believing in the gold. Sure, none had been found yet, he admitted in a presentation to fellow executives in 1609, but an Englishman who spoke Indian languages and had been on earlier expeditions said that "to the southwest of our old fort in Virginia, the Indians often informed him . . . there was a great melting of red metall. Beside, our own Indians have lately revealed either this or another rich mine . . . near certain mountains lying" just a bit west of the failed settlement.

No gold was found. Captain John Smith, looking for a navigable westward route to the Pacific rather than gold, was not completely exempt from gullibility - he reported as fact a native's claim that people on Chesapeake Bay hunt "apes in the mountains." But he famously did not believe in the dream of instant, easy mineral wealth. "There was no talk, no hope, no work, but dig gold, work gold, refine gold, and load gold," Smith wrote of his fellow, Jamestown colonists, “golden promises [that] made all men their slaves in hope of recompense." In fact, Jamestown ore they dug and refined and shipped to England turned out to be iron pyrite, fool's gold.

Anxious investors in London demanded the colonists produce at least one chunk of real gold. In 1610, three years into the operation, they dispatched a new man to set things right, who arrived just as the surviving colonists finally abandoned the dream and set sail home for England, Lord De La Warr persuaded them to disembark and buck up; he led a team inland to search for another rumored Indian gold mine, where De La Warr's men killed some Indians, and finally . . . found no gold.

The gold fantasy wasn't limited to colonists in the South. Those dispatched at the same time by the Plymouth Company, 120 of them, landed up on the Maine coast, also looking for gold and a faster route to Asia. They found signs of neither. But their desperation to believe the impossible is funny and sad. No gold so far, the colony president wrote home, but "the natives constantly affirm that in these parts there are nutmegs, mace and cinnamon." Tropical spices growing in New England? "They [also] positively assure me that . . . distant not more than seven days' journey from our fort [is] a sea large and wide and deep . . . which cannot be any other than the Southern Sea, reaching to the regions of China." Unlike their Virginia compatriots,

22

however, the English colonists in Maine quickly accommodated reality and admitted defeat. Half left a few months after arriving, the rest six months later. They were not credulous or imaginative enough to become Americans.

But . . . maybe they just hadn't talked to the right natives! Or looked in the right places! In 1614 yet another Plymouth Company expedition sailed to New England, this one exclusively in pursuit of gold. They had an inside man aboard, a native who'd been captured and enslaved by an earlier Plymouth Company ship off Cape Cod. The Indian had spent his entire captivity in London learning English and the nature of his captors' shiny metal fixation, so he concocted a story just for them: “There's a goldmine on my own island, he lied, “ and I'll take you back there to claim it. When the English anchored off Martha's Vineyard, he jumped ship, and his tribal brothers covered his escape with bow-and-arrow fire from canoes. The Englishmen realized they’d been played and sailed home.

Down in Virginia, meanwhile, more than six thousand people had emigrated to Jamestown by 1620, the equivalent of a midsize English city at the time. At least three-quarters had died, but not the abiding dream. People kept coming and believing, hopefulness becoming delusion. It was a gold rush with no gold. Fifteen years after Jamestown's founding, a colonist wrote a friend to request a shipment of nails, cutlery, vinegar, cheese - and also to make excuses for why he hadn't quite yet managed to get rich: "By reason of my sickness & weakness I 'was not able to travel up and down the hills and dales of these countries but doo now intend every day to walk up and down the hills for good minerals here is both gold [and] silver."

The sickness and weakness and death continued. Gold remained a chimera. Two decades into the seventeenth century, English America was a failing start-up, a vaporware tragedy and farce. But back in England the investors and their promotional agents continued printing posters, hyperbolic testimonials, and dozens of books and pamphlets, organizing lotteries, and fanning out hucksterish blue smoke. Thus the first English-speaking Americans tended to be the more wide eyed and desperately wishful. "Most of the 120,000 indentured servants and adventurers who sailed to the South in the seventeenth century," according to the University of Pennsylvania historian Walter McDougall's history of America, Freedom Just Around the Corner, "did not know what lay ahead but were taken in by the propaganda of the sponsors." The historian Daniel Boorstin went even further, suggesting that “American civilization [has] been shaped by 'the fact that there was a kind of natural selection here of those people who were willing to believe in advertising.'" Remember, question your perception.

23

Western civilization's first advertising campaign was created in order to inspire enaough dreamers and suckers to create America. Is fantasyland in our genes?

As a get-rich-quick enterprise, Virginia was a bust. The colonists who stayed resorted to the familiar drudgery of agriculture, although the cash crop that saved them was a harbinger of a certain future America - it was indigenous, novel, glamorous, inessential, psychoactive, and addictive: tobacco. This was the birth of the tobacco industry, introduced by the native Indians, and capitalized upon by the settlers.

Another leader of the colonization enthusiasts was Francis Bacon, an English government official and philosopher, who at the time was also laying foundations for science and the Enlightenment. He was bracingly clear-eyed about the New World project, and he seemed to understand better than any of his proto-American contemporaries the distorting power of wishful belief, how fantasy can trump fact. "The human understanding," he wrote in 1620,

“when it has once adopted an opinion (either as being the received opinion or as being agreeable to itself) draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else by some distinction sets aside and rejects; in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusions may remain inviolate. . . . And such is the way of all superstition, whether in astrology, dreams, omens, divine judgments, or the like; wherein men, having a delight in such vanities, mark the events where they are fulfilled, but where they fail, though this happen much oftener, neglect and pass them by.”

Was Bacon referring then to what is now known as our genetic hardwired cognitive and confirmation biases, leading to these neurorealities? And was Sir Walter Raleigh and argumentative theory pitching a paradise fantasyland of gold across the ocean to the King and the masses in England? Did truth matter?

In his London circles, Bacon said, it was all “gold, silver, and temporal profit" driving the colonization project, not "the propagation of the Christian faith." For the imminent next wave of English would-be Americans, however, propagating a particular set of Christian superstitions, omens and divine judgments were more than just lip-service cover for dreams of easy wealth. For them, the prospect of colonization was all about the export of their supernatural fantasies to the New World.

32

The God-Given Freedom to Believe in God

The Massachusetts Bay Colonies grew FAST, from a population of a thousand to forty thousand in its first decade or so. One of them was Anne Hutchinson, daughter of a minister, wife of a well-to-do merchant, mother of a dozen children, Boston neighbor of Governor Winthrop, and a charismatic, extremely impassioned Puritan. She promptly set herself up as a de facto preacher. Every week dozens of women came to the Hutchinsons' big house to hear her critiques of the previous Sunday's church sermons and ask questions about sin, salvation, and God: “Since the Lord decided before the beginning of time which of us will spend eternity with Him, she explained to her listeners, any one of us might hold a winning ticket, regardless of our status in the here and now. The clergy’s learning and degrees and titles give them, no special lock on godliness.”

But she didn't just argue the logic and quibble over the fine points of the beliefs they all shared. No, she gleamed with an absolute conviction, knew she was Heaven-bound, felt the truth in her gut. The Puritans in Massachusetts "were the first Americans to enact the paradigm that underlies all

33

romantic projects," as the historian Andrew Delbanco says: they "dared to assert the direct apprehension by the believer of the divine." Hutchinson took the paradigm and upped the ante, calling the leaders' bluff. People "look at her as a prophetess," Governor Winthrop anxiously wrote in his journal. She claimed to have some kind of sixth sense for divining who was or wasn't a member of God's special elect.

Men began attending the gatherings as well, and she added a second weekly session. Enlightened and emboldened, her followers took to walking out of church in the middle of sermons by ministers they weren't feeling. Anne Hutchinson, resident in America for only a thousand days, was leading a movement to make her colony of magical thinkers even more fervid. Protestantism had started as a breakaway movement of holier-than-thou zealots - and in the even-holier-than-thou zealots' state-of-the-art utopia, they now had a still-holier-than-thou mystic militant in their midst.

Once a faction of the colony's leaders signed on to Hutchinson's more radical, passionate, extra-pure Puritanism, she became problematic. Sure, individuals sometimes overflowed with the Holy Spirit. And yes, everybody's a Bible-reading amateur theologian; the "priesthood of all believers" made Protestants Protestants rather than sheeplike Catholics or crypto-Catholics. But come on, we've got a brand-new theocracy to run here (and at that moment a war to wage against a native tribe in Connecticut). Anne Hutchinson had gone rogue.

She was charged and tried for defaming ministers. Governor Winthrop served as chief judge. On the first day of her testimony in November 1637, she stayed within the bounds of Puritan intellectualism, batting scriptural references back and forth, arguing that her religious meetings weren't public events. She didn’t quite tell them she was godlier than they, but her contempt was clear. "We are your judges," Winthrop told her, "and not you ours." She fainted.

When her trial resumed the next day, she let it all hang out. It wasn't just the Bible that guided her but the Holy Spirit - that is, God, speaking to her personally, just as He had spoken to people in the Bible. It was, she told them, “an immediate revelation. . . . by the voice of his own spirit to my soul. . . .God had said to me . . . 'l am the same God that delivered Daniel out of the lion's den, I will also deliver thee.'” Governor Winthrop and his forty fellow judges had assembled to convict her of something, and now she'd made it easy. Furthermore, she threatened them and their misguided regime with God's own wrath: "Therefore take heed how you proceed against me - for I know that, for this you go about to do to me, God will ruin you and your posterity and this whole state."

34

“This is the thing that has been the root of all the mischief" Winthrop bellowed, pointing at her, and also: “I am persuaded that the revelation she brings forth is delusion.”

"Mistress Hutchinson," a once and future Massachusetts governor among the judges said during the trial, "is deluded by the Devil." And a witness against her, one of her fellow shipmates on the passage from England, testified that she'd made "very strange and witchlike" pronouncements when they'd landed in America three years earlier. The court might have brought a conviction for witchcraft and executed her. Instead, they threw her out of the colony.

In the modern era, Anne Hutchinson is inevitably portrayed as the first great American heroine, a feminist crusader for religious liberty and the victim of a show trial. Undoubtedly her gender made her freelance shamanism even more appalling and unacceptable. The trial transcript, dozens of male judges and witnesses versus one female defendant, is a horrible, hilarious episode of mansplaining. One minister testified that she "had rather been husband than a wife; and a preacher than a hearer."

But the intolerance she experienced isn't what makes Anne Hutchinson a prototypically American figure. Protestant communities in Europe surely would’ve punished or exiled her as well, and by global standards, Massachusetts was not an unusually oppressive place for women. No, Hutchinson is so American because she was so confident in herself, in her intuitions and idiosyncratic, subjective understanding of reality. She's so American because, unlike the worried, pointy-headed people around her, she didn't recognize ambiguity or admit to self-doubt. Her perceptions and beliefs were true because they were hers and because she felt them so thoroughly to be true. They weren't mere theories and opinions delivered by her Oxford-and Cambridge-educated antagonists. Hutchinson didn't have to study any book but the Bible to arrive at the truth. Because she felt it. She knew it. The great historian of Puritanism Perry Miller refers to her "fanatical anti-intellectualism"- in other words, a prototypical Fantasyland American.

The American Puritans were the Protestant avant-garde, and she was the most avant of all – a dissident persecuted and banished by a corrupt and self-serving elite, a self-righteous individual whose individual imagination was all that mattered. By claiming she had personal access to God, Hutchinson took a big piece of the nonconformist Protestant idea to an even more fantastical and perfectly American extreme.

It's hard for us to understand or empathize with our founding Puritans,

35

not because of their wild religious beliefs - many of which a great many Americans still share - but because of their ferocious insistence on discipline. Alone among the Puritans, Anne Hutchinson is the one with whom American sensibilities today can connect, because America is now a nation where every individual is gloriously free to construct any version of reality he or she devoutly believes to be true. American Christianity in the twenty-first century resembles Hutchinson's version more than it does the official Christianity of her time.

In other words, Anne Hutchinson lost her battle in Cambridge but would finally win the war. For the Puritan leaders, it was their way or the highway. But in America there was an infinity of highways and new places not so far away where outcast true believers could move.

While Quaker Pennsylvania soon welcomed Christian zealots of almost every kind, the Quakers' famous civic reasonableness - tolerant, democratic, pacifist, protofeminist, abolitionist - tends to obscure their own founding zealotry: each person could directly commune with God, which variously took the form of prophecies, trancelike rants, and convulsions.

Hutchinson's fellow charismatic Massachusetts Puritan, the young minister Roger Williams, claimed no wizardly superpowers. Nevertheless, he was also problematic for the Boston theocrats - he disapproved of theocracy, and his hatred of the Church of England was a bit too self-righteously fervent. They convicted him of heresy and sedition shortly before they banished Hutchinson. He moved forty miles south to start a new colony, which he named for God's blessed omnipotence, Providence. Williams and Hutchinson were thus both key inventors of American individualism. He disagreed with the religious nonsense you spouted, but he would defend to the death your right to spout it; she was the crackpot case study for extreme freedom of thought and speech, insisting she be allowed to believe and tell people she had magical powers. Which Williams was willing to let her do in Providence, where she moved.

Today we tell ourselves a story of America's progress toward freedom of thought and a happy ending. Williams in Rhode Island and the Quaker William Penn in his new colony were indeed heroic progressives , separating the state from any one church. The Massachusetts theocracy softened and eventually dissolved. Then a century later came Thomas Jefferson's Virginia statute for Religious Freedom, the constitution, and the First Amendment.

36

All that was indeed progress. Disbelief was eventually permitted, at least Iegally.

But during our founding 1600s, as giants walked in Europe and the Age of Reason dawned - Shakespeare, Galileo, Bacon, Isaac Newton, Rene Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza - America was a primitive outlier. Individual freedom of thought in early America was specifically about the freedom to believe whatever supernaturalism you wished, you could generate whatever neuroreality you wanted. Four centuries later that has been a freedom, revived and unfettered and run amok, driving America's transformation.

39

Imaginary Friends and Enemies; The Early Satanic Panics

Witchcraft didn’t officially exist in the Middle ages, but as soon as protestantism emerged, so did alleged witches and witch hunts.

40

Once the Puritans were in their wonderful and horrifying new promised land, fulfilling God's plan and fighting Satan, witches were probably inevitable. In the 1640s the Puritans in Connecticut and Massachusetts began indicting a couple of people each year for witchcraft. But they fined and banished and acquitted more witches than they hung, thus proving to themselves their moderation. That early hysteria over sorcery subsided, and for two generations New England wasn't executing witches.

But then in 1689, at the conclusion of decades of religious struggle back in England, parliament passed the Act of Toleration, which obliged the Puritans in America to allow their fellow Americans to believe and practice almost any version of Protestantism. The grandchildren of the original great dissenters now had to permit some dissent - and therefore to become just one more Christian sect among burgeoning Christian sects. Some of them detected Satan's hand in this existential demotion. But . . . witches: witches didn't need to be tolerated. Young Reverend Cotton Mather had recently published an essay describing the slippery slope of faithlessness: once you started disbelieving in witches, what was to stop you from disbelieving in God? The year the Toleration Act became Iaw, he published another book, Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions, about a recent episode of witchcraft and enchanted children in Boston.

Mather's handy guide was a bestseller, and one of its readers was the minister of the First Church in Salem, the New England Puritans' oldest. In the winter of 1691, his nine-year-old daughter began acting strangely - screaming, barking, burning up with fever. After other girls displayed similar "distempers," the cause became clear – witchcraft - and some sorceresses were identified: the minister's Caribbean servant, plus two other local women, one very poor and the other a non-churchgoer. More girls turned weird, a few other women were accused, then men, then dozens more people.

Cotton Mather, the golden-boy witch expert in Boston, weighed in. He declared that "spectral evidence," tricky as it was, should be allowed at the trials - that is, prosecution witnesses' accounts of their dreams and supernatural visions of ghostly witches and demons. After the first convicted witch was hung, Mather suggested the court use spectral evidence carefully, but it continued to be prime evidence. and he encouraged the judges in their "speedy and vigorous prosecutions." Most of the several dozen accusers were girls. In four months more than two hundred trials produced dozens of guilty verdicts, mostly of women, and at least twenty witches and sorcerers (and two satanic pet dogs) were executed. A few, others died in jail. The total population of the towns of Salem and Andover was only 2400.

41

As the madness reached its peak that summer, the Reverend Increase Mather, Cotton’s Father and a leader of the colony, returned from a trip to England and promptly hit the brakes. After eight witches and sorcerers were hanged in Salem in one day, the most so far, he wrote a tract called Cases of Conscience and had it approved by the Puritan clerical association. Presently his friend the governor disbanded the Salem witchcraft court.

Ever since, Cases of Conscience has been regarded as the great turning point in the restoration of reason in colonial America. Its title seems appealingly liberal, and its most famous line makes us think Salem was a completely anomalous moment of temporary insanity: "lt were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person should be condemned." But the seldom-quoted complete title of the book is a giveaway: Cases of Conscience concerning evil SPIRITS Personating Men, Witchcrafts, Infallible Proofs of Guilt in such as are accused with that Crime. It's an explanation of how Satan actually works, filled with secondhand tales of evil magic from around the world, such as a new report of "a Venetian Jew" who knew "how to make a Magical Glass which should represent any Person or thing according as he should desire." For Increase Mather, the problem in Salem was that Satan had bewitched some of the accusers into making false accusations - the devil made the good people do it. As the historian Edmund Morgan has written, "In 1692 virtually no one in New England . . . disbelieved in witches."

Although the special witchcraft court adjourned, the chief judge from Salem was also the chief judge of a replacement court. And although to his

42

great disappointment spectral evidence was no longer admissible, for months his new court continued trying people for witchcraft, and he signed the death warrants for three more convicted witches. The following year he was elected governor of Massachusetts. This was William Stoughton.

Increase Mather never fully condemned the Salem episode, and his son backpedaled hardly at all. Although mistakes were made, Cotton eventually admitted - decades later, deep into the eighteenth century, in the lifetime of his neighbor Ben Franklin - he did not stop defending the witchcraft trials and executions.

The big piece of secular conventional wisdom about Protestantism has been that it gave a self-righteous oomph to moneymaking and capitalism - hard work accrues to God's glory, success looks like a sign of His grace. But it seems clear to me the deeper, broader, and more enduring influence of American Protestantism was the permission it gave to dream up new supernatural or otherwise untrue understandings of reality, untrue neurorealities, and believe them with passionate certainty.

Science was being invented at the time. Like science, Protestantism was powered by skepticism of the established religious paradigms, which were to be revised or rejected - but unlike science, the old paradigms were to be replaced by new fixed truth. The scientific method is unceasingly skeptical, each truth understood as a partial, provisional best-we-can-do-for-the- moment understanding of reality. In their travesty of science, Protestant true believers scrutinized the natural world to deduce the underlying godly or satanic causes of every strange effect, from comets to hurricanes to Indian attacks to unusual illnesses and deaths. For believers in the new American religion, the truth was out there: everything happened for a purpose, and the purpose wasn't so hard to figure out.

This country began as an empty vessel for pursuing fantasies of easy wealth or utopia or eternal life - a vessel of such spaciousness that an assortment of new fantasies could be spun off perpetually. That had never happened before. Ordinary individuals took the initiative and improvised a country out of a wilderness, reshaped the world. That had never happened before, either. In just a century, the (white) American population grew from a few thousand to a million people, and it continued doubling every couple of decades. This improbable and peculiar new place thrived. The dream - that is, any of several and then dozens and finally hundreds of coexisting American fantasies - those neurorealities - seemed to be coming true.

Note now we have political hucksters pitching untruths, falsehoods and flat out lies, and a significant portion of the electorate stands by those statements. A prominent phrase in the late 1800s states this precisely: "There's a sucker born every minute." And Vladimir Lenon coined the term "useful idiot", someone who is susceptible tp propoganda and is cynically misused for political and partisan gains. It appears now that a significant protion of the US population has such neurorealities, which is representative and a result of the early gene pool comprised of the original gold minded settlers and the early Protestant settlers, and their fantastic or supernatural, or otherwise untrue neaurorealities. It's in America's gene's.

Recall, neuroreality is the perception of reality and our surroundings generated by the brain and it’s 100 billion neurons. This perception is not the actual reality, it is only the reality as perceived by the 100 billion neurons in your brain firing away generating such with the input from the 5 senses. That input gets processed by the 100 billion neurons in your brain and that generates your consciousness, your neuroreality.

Video Summary

26 minute video

90 minute read