Synthisophy

Skinwalkers - Chapter 18

The following are direct quotes from the book Tribe, On Homecoming and Belonging, by Sebastian Junger, May 2016, except for statements in italic added.

The ultimate act of disaffiliation isn’t littering or fraud, of course, but violence against your own people. When the Navajo Nation—the Diné, in their language—were rounded up and confined to a reservation in the 1860s, a terrifying phenomenon became more prominent in their culture. The warrior skills that had protected the Diné for thousands of years were no longer relevant in this dismal new era, and people worried that those same skills would now be turned inward, against society. That strengthened their belief in what were known as skinwalkers, or yee naaldlooshii.

Skinwalkers were almost always male and wore the pelt of a sacred animal so that they could subvert that animal’s powers to kill people in the community. They could travel impossibly fast across the desert and their eyes glowed like coals and they could supposedly paralyze you with a single look. They were thought to attack remote homesteads at night and kill people and sometimes eat their bodies. People were still scared of skinwalkers when I lived on the Navajo Reservation in 1983, and frankly, by the time I left, I was too.

Virtually every culture in the world has its version of the skinwalker myth. In Europe, for example, they are called werewolves (literally “man-wolf” in Old English). The myth addresses a fundamental fear in human society: that you can defend against external enemies but still remain vulnerable to one lone madman in your midst. Anglo-American culture doesn’t recognize the skinwalker threat but has its own version. Starting in the early 1980s, the frequency of rampage shootings in the United States began to rise more and more rapidly until it doubled around 2006. Rampages are usually defined as attacks where people are randomly targeted and four or more are killed in one place, usually shot to death by a lone gunman. As such, those crimes conform almost exactly to the kind of threat that the Navajo seemed most to fear on the reservation: murder and mayhem committed by an individual who has rejected all social bonds and attacks people at their most vulnerable and unprepared. For modern society, that would mean not in their log hogans but in movie theaters, schools, shopping malls, places of worship, or simply walking down the street.

Here is a list of skinwalkers, and their shooting rampages in the USA over the last 30 years. Note that from 1988 to 1997 there were 6; from 1998 to 2007 there were 9; from 2008 to 2017 there were 24. Why does it appear that over the last 10 years our society is generating a sharp increase in skinwalkers, individuals committing murder and mayhem who have rejected all social bonds and attack people at their most vulnerable and unprepared? Perhaps it is because, as Sebastion Junger stated, this “shows how completely detribalized this country has become.” Our neurological genetic predisposition, the warrior ethos, all for 1 and 1 for all, is no longer relevant in modern life. As individuals in society it appears we are now very far from our evolutionary roots.

In 2013, areport from the Congressional Research Service, known as Congress's think tank, described mass shootings as those in which shooters "select victims somewhat indiscriminately" and kill four or more people.

From: http://timelines.latimes.com/deadliest-shooting-rampages/

Mass shootings over last 30 years until October 1, 2017. And recent news from October 2 to December 31, 2017.

November 14, 2017: Rampaging through a small Northern California town, a gunman took aim on Tuesday at people at an elementary school and several other locations, killing at least four and wounding at least 10 before he was fatally shot by police, the local sheriff’s office said.

November 5, 2017: Devin Patrick Kelley carried out the deadliest mass shooting in Texas history on Sunday, killing 25 people and an unborn child at First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, near San Antonio.

October 1, 2017: 58 killed, more than 500 injured: Las Vegas

More than 50 people were killed and at least 500 others injured when a gunman opened fire at a country music festival near the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip, authorities said. Police said the suspect, 64-year-old Stephen Paddock, a resident of Mesquite, Nev., was was found dead after a SWAT team burst into the hotel room from which he was firing at the crowd.

Jan. 6, 2017: 5 killed, 6 injured: Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

After taking a flight to Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport in Florida, a man retrieves a gun from his luggage in baggage claim, loads it and opens fire, killing five people near a baggage carousel and wounding six others. Dozens more are injured in the ensuing panic. Esteban Santiago, a 26-year-old Iraq war veteran from Anchorage, Alaska, has pleaded not guilty to 22 federal charges.

May 28, 2017: 8 killed, Lincoln County, Miss. A Mississippi man went on a shooting spree overnight, killing a sheriff's deputy and seven other people in three separate locations in rural Lincoln County before the suspect was taken into custody by police, authorities said on Sunday.

Sept. 23, 2016: 5 killed: Burlington, Wash.

A gunman enters the cosmetics area of a Macy’s store near Seattle and fatally shoots an employee and four shoppers at close range. Authorities say Arcan Cetin, a 20-year-old fast-food worker, used a semi-automatic Ruger .22 rifle that he stole from his stepfather’s closet.

June 12, 2016: 49 killed, 58 injured in Orlando nightclub shooting

The United States suffered one of the worst mass shootings in its modern history when 49 people were killed and 58 injured in Orlando, Fla., after a gunman stormed into a packed gay nightclub. The gunman was killed by a SWAT team after taking hostages at Pulse, a popular gay club. He was preliminarily identified as 29-year-old Omar Mateen.

Dec. 2, 2015: 14 killed, 22 injured: San Bernardino, Calif.

Two assailants killed 14 people and wounded 22 others in a shooting at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino. The two attackers, who were married, were killed in a gun battle with police. They were U.S.-born Syed Rizwan Farook and Pakistan national Tashfeen Malik, and had an arsenal of ammunition and pipe bombs in their Redlands home.

Nov. 29, 2015: 3 killed, 9 injured: Colorado Springs, Colo.

A gunman entered a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs, Colo., and started firing.

Police named Robert Lewis Dear as the suspect in the attacks.

Oct. 1, 2015: 9 killed, 9 injured: Roseburg, Ore.

Christopher Sean Harper-Mercer shot and killed eight fellow students and a teacher at Umpqua Community College. Authorities described Harper-Mercer, who recently had moved to Oregon from Southern California, as a “hate-filled” individual with anti-religion and white supremacist leanings who had long struggled with mental health issues.

July 16, 2015: 5 killed, 3 injured: Chattanooga, Tenn. A gunman opened fire on two military centers more than seven miles apart, killing four Marines and a Navy sailor. A man identified by federal authorities as Mohammod Youssuf Abdulazeez, 24, sprayed dozens of bullets at a military recruiting center, then drove to a Navy-Marine training facility and opened fire again before he was killed.

June 18, 2015: 9 killed: Charleston, S.C.

Dylann Storm Roof is charged with nine counts of murder and three counts of attempted murder in an attack that killed nine people at a historic black church in Charleston, S.C. Authorities say Roof, a suspected white supremacist, started firing on a group gathered at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church after first praying with them. He fled authorities before being arrested in North Carolina.

May 23, 2014: 6 killed, 7 injured: Isla Vista, Calif.

Elliot Rodger, 22, meticulously planned his deadly attack on the Isla Vista community for more than a year, spending thousands of dollars in order to arm and train himself to kill as many people as possible, according to a report released by the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office. Rodger killed six people before shooting himself.

April 2, 2014: 3 killed; 16 injured: Ft. Hood, Texas

A gunman at Fort Hood, the scene of a deadly 2009 rampage, kills three people and injures 16 others, according to military officials. The gunman is dead at the scene.

Sept. 16, 2013: 12 killed, 3 injured: Washington, D.C. Aaron Alexis, a Navy contractor and former Navy enlisted man, shoots and kills 12 people and engages police in a running firefight through the sprawling Washington Navy Yard. He is shot and killed by authorities.

June 7, 2013: 5 killed: Santa Monica

John Zawahri, an unemployed 23-year-old, kills five people in an attack that starts at his father’s home and ends at Santa Monica College, where he is fatally shot by police in the school’s library.

Dec. 14, 2012: 27 killed, one injured: Newtown, Conn.

A gunman forces his way into Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. and shoots and kills 20 first graders and six adults. The shooter, Adam Lanza, 20, kills himself at the scene. Lanza also killed his mother at the home they shared, prior to his shooting rampage.

Aug. 5, 2012: 6 killed, 3 injured: Oak Creek, Wis.

Wade Michael Page fatally shoots six people at a Sikh temple before he is shot by a police officer. Page, an Army veteran who was a “psychological operations specialist,” committed suicide after he was wounded. Page was a member of a white supremacist band called End Apathy and his views led federal officials to treat the shooting as an act of domestic terrorism.

July 20, 2012: 12 killed, 58 injured: Aurora, Colo.

James Holmes, 24, is taken into custody in the parking lot outside the Century 16 movie theater after a post-midnight attack in Aurora, Colo. Holmes allegedly entered the theater through an exit door about half an hour into the local premiere of “The Dark Knight Rises.”

April 2, 2012: 7 killed, 3 injured: Oakland

One L. Goh, 43, a former student at a Oikos University, a small Christian college, allegedly opens fire in the middle of a classroom leaving seven people dead and three wounded.

Jan. 8, 2011: 6 killed, 11 injured: Tucson, Ariz.

Jared Lee Loughner, 22, allegedly shoots Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in the head during a meet-and-greet with constituents at a Tucson supermarket. Six people are killed and 11 others wounded.

Nov. 5, 2009: 13 killed, 32 injured: Ft. Hood, Texas

Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, an Army psychiatrist, allegedly shoots and kills 13 people and injures 32 others in a rampage at Ft. Hood, where he is based. Authorities allege that Hasan was exchanging emails with Muslim extremists including American-born radical Anwar Awlaki.

April 3, 2009: 13 killed, 4 injured: Binghamton, N.Y.

Jiverly Voong, 41, shoots and kills 13 people and seriously wounds four others before apparently committing suicide at the American Civic Assn., an immigration services center, in Binghamton, N.Y.

Feb. 14, 2008: 5 killed, 16 injured: Dekalb, Ill.

Steven Kazmierczak, dressed all in black, steps on stage in a lecture hall at Northern Illinois University and opens fire on a geology class. Five students are killed and 16 wounded before Kazmierczak kills himself on the lecture hall stage.

Dec. 5, 2007: 8 killed, 4 injured: Omaha

Robert Hawkins, 19, sprays an Omaha shopping mall with gunfire as holiday shoppers scatter in terror. He kills eight people and wounds four others before taking his own life. Authorities report he left several suicide notes.

April 16, 2007: 32 killed, 17 injured: Blacksburg, Va.

Seung-hui Cho, a 23-year-old Virginia Tech senior, opens fire on campus, killing 32 people in a dorm and an academic building in attacks more than two hours apart. Cho takes his life after the second incident.

Feb. 12, 2007: 5 killed, 4 injured: Salt Lake City

Sulejman Talovic, 18, wearing a trenchcoat and carrying a shotgun, sprays a popular Salt Lake City shopping mall. Witnesses say he displays no emotion while killing five people and wounding four others.

Oct. 2, 2006: 5 killed, 5 injured: Nickel Mines, Pa.

Charles Carl Roberts IV, a milk truck driver armed with a small arsenal, bursts into a one-room schoolhouse and kills five Amish girls. He kills himself as police storm the building.

July 8, 2003: 5 killed, 9 injured: Meridian, Miss.

Doug Williams, 48, a production assemblyman for 19 years at Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Co., goes on a rampage at the defense plant, fatally shooting five and wounding nine before taking his own life with a shotgun.

Dec. 26, 2000: 7 killed: Wakefield, Mass.

Michael McDermott, a 42-year-old software tester shoots and kills seven co-workers at the Internet consulting firm where he is employed. McDermott, who is arrested at the offices of Edgewater Technology Inc., apparently was enraged because his salary was about to be garnished to satisfy tax claims by the Internal Revenue Service. He uses three weapons in his attack.

Sept. 15, 1999: 7 killed, 7 injured: Fort Worth

Larry Gene Ashbrook opens fire inside the crowded chapel of the Wedgwood Baptist Church. Worshipers, thinking at first that it must be a prank, keep singing. But when they realize what is happening, they dive to the floor and scrunch under pews, terrified and silent as the gunfire continues. Seven people are killed before Ashbrook takes his own life.

April 20, 1999: 13 killed, 24 injured: Columbine, Colo.

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, students at Columbine High, open fire at the school, killing a dozen students and a teacher and causing injury to two dozen others before taking their own lives.

March 24, 1998: 5 killed, 10 injured: Jonesboro, Ark.

Middle school students Mitchell Johnson and Andrew Golden pull a fire alarm at their school in a small rural Arkansas community and then open fire on students and teachers using an arsenal they had stashed in the nearby woods. Four students and a teacher who tried shield the children are killed and 10 others are injured. Because of their ages, Mitchell. 13, and Andrew, 11, are sentenced to confinement in a juvenile facility until they turn 21.

Dec. 7, 1993: 6 killed, 19 injured: Garden City, N.Y.

Colin Ferguson shoots and kills six passengers and wounds 19 others on a Long Island Rail Road commuter train before being stopped by other riders. Ferguson is later sentenced to life in prison.

July 1, 1993: 8 killed, 6 injured: San Francisco

Gian Luigi Ferri, 55, kills eight people in an office building in San Francisco’s financial district. His rampage begins in the 34th-floor offices of Pettit & Martin, an international law firm, and ends in a stairwell between the 29th and 30th floors where he encounters police and shoots himself.

May 1, 1992: 4 killed, 10 injured: Olivehurst, Calif.

Eric Houston, a 20-year-old unemployed computer assembler, invades Lindhurst High School and opens fire, killing his former teacher Robert Brens and three students and wounding 10 others.

Oct. 16, 1991: 22 killed, 20 injured: Killeen, Texas

George Jo Hennard, 35, crashes his pickup truck into a Luby’s cafeteria crowded with lunchtime patrons and begins firing indiscriminately with a semiautomatic pistol, killing 22 people. Hennard is later found dead of a gunshot wound in a restaurant restroom.

June 18, 1990: 10 killed, 4 injured: Jacksonville, Fla.

James E. Pough, a 42-year-old day laborer apparently distraught over the repossession of his car, walks into the offices of General Motors Acceptance Corp. and opens fire, killing seven employees and one customer before fatally shooting himself.

Jan. 17, 1989: 5 killed, 29 injured: Stockton, Calif.

Patrick Edward Purdy turns a powerful assault rifle on a crowded school playground, killing five children and wounding 29 more. Purdy, who also killed himself, had been a student at the school from kindergarten through third grade.Police officials described Purdy as a troubled drifter in his mid-20s with a history of relatively minor brushes with the law. The midday attack lasted only minutes.

July 18, 1984: 21 killed, 19 injured: San Ysidro, Calif.

James Oliver Huberty, a 41-year-old out-of-work security guard, kills 21 employees and customers at a McDonald’s restaurant. Huberty is fatally shot by a police sniper perched on the roof of a nearby post office.

Synthisophy

Integrate the Wisdoms of History into Present Culture

Addressing the polarized political climate in the USA

Add Text Here...

.

Afterword

Here is an additional Chapter published in March of 2023 after the original 30 Chapters on Synthisophy were published on-line in full in August of 2018.

Chapter 31: Artificial Intelligence and Polarization + Thesis 5

Recall the last 2 diagrams and paragraphs in Chapter 30:

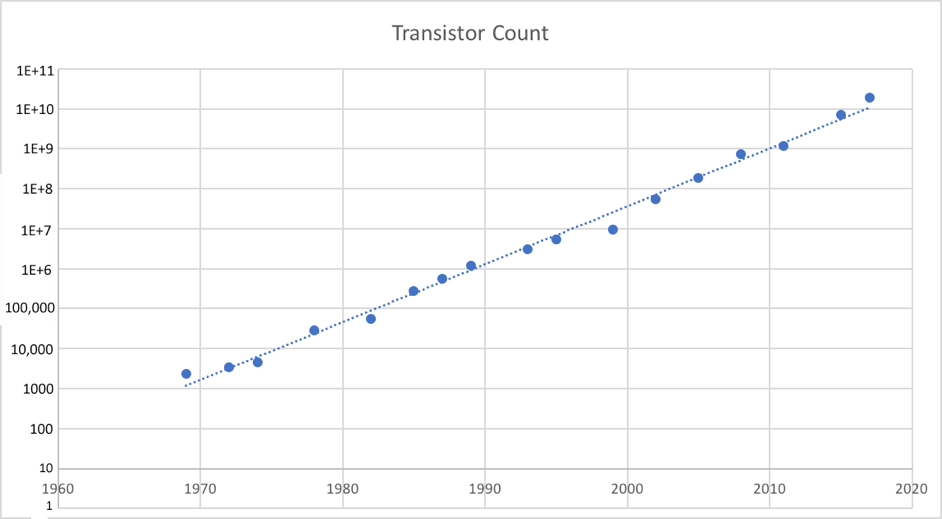

Chart 1

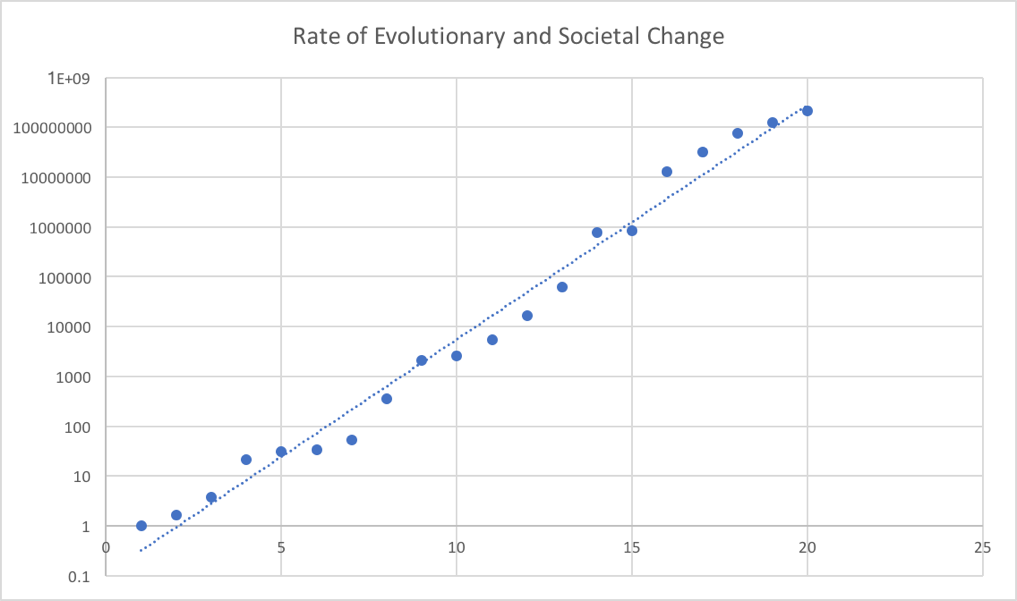

Chart 2

What does this logarithmic similarity between computer transistor count in the last 50 years (Chart 1) and evolutionary and societal change over the last 3.8 billion years (Chart 2) mean? At this point in time this similarity means that we are in the early stage of huge societal changes as a result of the digital revolution, and that it may be in our best interest to become less polarized and more rational in order to best choose our destiny as a society.

That said, the convergence of the human/societal evolution and the transistor count/digital revolution may at some point in the not too distant future reach the point of singularity, when computers and artificial intelligence equal that of the human brain, after which computers may then surpass human intelligence.

Note now that artificial Intelligence appears to be a major contributor to the polarization present in our society. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and others use algorithmic programs that learn what keeps users engaged and on-line, with total disregard for its impact on society – it’s a digital machine, it doesn’t “know” what it’s doing. But the humans that created it did, and they did it anyway, to make money. Now the neurons in the human brain have been rewired, and not for the better.

The following evidence for the above statements are direct quotes from the book The Chaos Machine, by Max Fisher, September 2022, except for references to the 30 Chapters in Synthisophy and additional statements added in italic. Some statements bolded for emphasis. Page numbers added for reference.

p7

It was a strangely incomplete picture of how Facebook works. Many at the company seemed almost unaware that the platform’s algorithms and design deliberately shape users’ experiences and incentives, and therefore the users themselves. These elements are the core of the product, the reason that hundreds of programmers buzzed around us as we talked. It was like walking into a cigarette factory and having executives tell you they couldn’t understand why people kept complaining about the health impacts of the little cardboard boxes that they sold. See Chapters 17, 19

p8

Within Facebook’s muralled walls, though, belief in the product as a force for good seemed unshakable. The core Silicon Valley ideal that getting people to spend more and more time online will enrich their minds and better the world held especially firm among the engineers who ultimately make and shape the products. “As we have greater reach, as we have more people engaging, that raises the stakes,” a senior engineer on Facebook’s all-important news feed said. “But I also think that there’s greater opportunity for people to be exposed to new ideas.” Any risks created by the platform’s mission to maximize user engagement would be engineered out, she assured me.

I later learned that, a short time before my visit, some Facebook researchers, appointed internally to study their technology’s effects, in response to growing suspicion that the site might be worsening America’s political divisions, had warned internally that the platform was doing exactly what the company’s executives had, in our conversations, shrugged off. “Our algorithms exploit the human brain’s attraction to divisiveness,” the researchers warned in a 2018 presentation later leaked to the Wall Street Journal. In fact, the presentation continued, Facebook’s systems were designed in a way that delivered users “more and more divisive content in an effort to gain user attention & increase time on the platform.” Executives shelved the research and largely rejected its recommendations, which called for tweaking the promotional systems that choose what users see in ways that might have reduced their time online. The question I had brought to Facebook’s corridors—what are the consequences of routing an ever-growing share of all politics, information, and human social relations through online platforms expressly designed to manipulate attention?—was plainly taboo here. See Chapters 6,7,15,22-25, 28

The months after my visit coincided with what was then the greatest public backlash in Silicon Valley’s history. The social media giants faced congressional hearings, foreign regulation, multibillion-dollar fines, and threats of forcible breakup. Public figures routinely referred to the companies as one of the gravest threats of our time. In response, the companies’ leaders pledged to confront the harms flowing from their services. They unveiled election-integrity war rooms and updated content-review policies. But their business model—keeping people glued to their platforms as many hours a day as possible—and the underlying technology deployed to achieve this goal remained largely unchanged. And while the problems they’d promised to solve only worsened, they made more money than ever.

p10

In summer 2020, an independent audit of Facebook, commissioned by the company under pressure from civil rights groups, concluded that the platform was everything its executives had insisted to me it was not. Its policies permitted rampant misinformation that could undermine elections. Its algorithms and recommendation systems were “driving people toward self-reinforcing echo chambers of extremism,” training them to hate. Perhaps most damning, the report concluded that the company did not understand how its own products affected its billions of users. See Chapters 6,7,15,22-25, 28

p11

The early conventional wisdom, that social media promotes sensationalism and outrage, while accurate, turned out to drastically understate things. An ever-growing pool of evidence, gathered by dozens of academics, reporters, whistleblowers, and concerned citizens, suggests that its impact is far more profound. This technology exerts such a powerful pull on our psychology and our identity, and is so pervasive in our lives, that it changes how we think, behave, and relate to one another. The neurons in the human brain have been rewired. The effect, multiplied across billions of users, has been to change society itself.

p13

RENÉE DIRESTA HAD her infant on her knee when she realized that social networks were bringing out something dangerous in people, something already reaching invisibly into her and her son’s lives. It was 2014, and DiResta had only recently arrived in Silicon Valley, there to scout startups for an investment firm. She was still an analyst at heart, from her years both on Wall Street and, before that, at an intelligence agency she hints was the CIA. To keep her mind agile, she filled her downtime with elaborate research projects, the way others might do a crossword in bed.

Though her investment work in Silicon Valley focused on hardware, she’d picked up enough about social media to understand what she’d found in her Facebook searches. The reason the system pushed the conspiratorial outliers so hard, she came to realize, was engagement. Social media platforms surfaced whatever content their automated systems had concluded would maximize users’ activity online, thereby allowing the company to sell more ads. See Chapter 28. A mother who accepts that vaccines are safe has little reason to spend much time discussing the subject online. Like-minded parenting groups she joins, while large, might be relatively quiet. But a mother who suspects a vast medical conspiracy imperiling her children, DiResta saw, might spend hours researching the subject. She is also likely to seek out allies, sharing information and coordinating action to fight back. To the A.I. governing a social media platform, the conclusion is obvious: moms interested in health issues will come to spend vastly more time online if they join anti-vaccine groups. Therefore, promoting them, through whatever method wins those users’ notice, will boost engagement. If she was right, DiResta knew, then Facebook wasn’t just indulging anti-vaccine extremists. It was creating them.

p24

Parker prided himself as a hacker, as did much of the Silicon Valley generation that arose in the 1990s, when the term still bespoke a kind of counterculture cool. Most actually built corporate software. But Parker had cofounded Napster, a file-sharing program whose users distributed so much pirated music that, by the time lawsuits shut it down two years after launching, it had irrevocably damaged the music business. Parker argued he’d forced the industry to evolve by exploiting its lethargy in moving online. Many of its artists and executives, however, saw him as a parasite.

Facebook’s strategy, as he described it, was not so different from Napster’s. But rather than exploiting weaknesses in the music industry, it would do so for the human mind. “The thought process that went into building these applications,” Parker told the media conference, “was all about, ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?’” To do that, he said, “We need to sort of give you a little dopamine

p25

hit every once in a while, because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post or whatever. And that’s going to get you to contribute more content, and that’s going to get you more likes and comments.” He termed this the “social-validation feedback loop,” calling it “exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” He and Zuckerberg “understood this” from the beginning, he said, and “we did it anyway.” See Chapters 6,7,28

Throughout the Valley, this exploitation, far from some dark secret, was openly discussed as an exciting tool for business growth. The term of art is “persuasion”: training consumers to alter their behavior in ways that serve the bottom line. Stanford University had operated a Persuasive Tech Lab since 1997. In 2007, a single semester’s worth of student projects generated $1 million in advertising revenue.

“How do companies, producing little more than bits of code displayed on a screen, seemingly control users’ minds?” Nir Eyal, a prominent Valley product consultant, asked in his 2014 book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. “Our actions have been engineered,” he explained. Services like Twitter and YouTube “habitually alter our everyday behavior, just as their designers intended.”

One of Eyal’s favorite models is the slot machine. It is designed to answer your every action with visual, auditory, and tactile feedback. A ping when you insert a coin. A ka- chunk when you pull the lever. A flash of colored light when you release it. This is known as Pavlovian conditioning, named after the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, who rang a bell each time he fed his dog, until, eventually, the bell alone sent his dog’s stomach churning and saliva glands pulsing, as if it could no longer differentiate the chiming of a bell from the physical sensation of eating. Slot machines work the same way, training your mind to conflate the thrill of winning with its mechanical clangs and buzzes. The act of pulling the lever, once meaningless, becomes pleasurable in itself.

The reason is a neurological chemical called dopamine, the same one Parker had referenced at the media conference. Your brain releases small

p26

amounts of it when you fulfill some basic need, whether biological (hunger, sex) or social (affection, validation). Dopamine creates a positive association with whatever behaviors prompted its release, training you to repeat them. But when that dopamine reward system gets hijacked, it can compel you to repeat self-destructive behaviors. To place one more bet, binge on alcohol—or spend hours on apps even when they make you unhappy. See Chapters 6,7,28

Dopamine is social media’s accomplice inside your brain. It’s why your smartphone looks and feels like a slot machine, pulsing with colorful notification badges, whoosh sounds, and gentle vibrations. Those stimuli are neurologically meaningless on their own. But your phone pairs them with activities, like texting a friend or looking at photos, that are naturally rewarding.

Social apps hijack a compulsion—a need to connect—that can be even more powerful than hunger or greed. Eyal describes a hypothetical woman, Barbra, who logs on to Facebook to see a photo uploaded by a family member. As she clicks through more photos or comments in response, her brain conflates feeling connected to people she loves with the bleeps and flashes of Facebook’s interface. “Over time,” Eyal writes, “Barbra begins to associate Facebook with her need for social connection.” She learns to serve that need with a behavior— using Facebook—that in fact will rarely fulfill it.

Soon after Facebook’s news-feed breakthrough, the major social media platforms converged on what Eyal called one of the casino’s most powerful secrets: intermittent variable reinforcement. The concept, while sounding esoteric, is devilishly simple. The psychologist B. F. Skinner found that if he assigned a human subject a repeatable task—solving a simple puzzle, say—and rewarded her every time she completed it, she would usually comply, but would stop right after he stopped rewarding her. But if he doled out the reward only sometimes, and randomized its size, then she would complete the task far more consistently, even doggedly. And she would keep completing the task long after the rewards had stopped altogether—as if chasing even the possibility of a reward compulsively.

p27

Unlike slot machines, which are rarely at hand in our day- to-day lives, social media apps are some of the most easily accessible products on earth. It’s a casino that fits in your pocket, which is how we slowly train ourselves to answer any dip in our happiness with a pull at the most ubiquitous slot machine in history. The average American checks their smartphone 150 times per day, often to open social media. We don’t do this because compulsively checking social media apps makes us happy. In 2018, a team of economists offered users different amounts of money to deactivate their account for four weeks, looking for the threshold at which at least half of them would say yes. The number turned out to be high: $180. But the people who deactivated experienced more happiness, less anxiety, and greater life satisfaction. After the experiment was over, they used the app less than they had before.

Why had these subjects been so resistant to give up a product that made them unhappy? Their behavior, the economists wrote, was “consistent with standard habit formation models”—i.e., with addiction—leading to “sub- optimal consumption choices.” A clinical way of saying the subjects had been trained to act against their own interests.

p29

Human beings are some of the most complex social animals on earth. We evolved to live in leaderless collectives far larger than those of our fellow primates: up to about 150 members. See Chapters 11,12,14,28. As individuals, our ability to thrive depended on how well we navigated those 149 relationships—not to mention all of our peers’ relationships with one another. If the group valued us, we could count on support, resources, and probably a mate. If it didn’t, we might get none of those. It was a matter of survival, physically and genetically. Over millions of years, those pressures selected for people who are sensitive to and skilled at maximizing their standing. It’s what the anthropologist Brian Hare called “survival of the friendliest.” The result was the development of a sociometer: a tendency to unconsciously monitor how other people in our community seem to perceive us. We process that information in the form of self-esteem and such related emotions as pride, shame, or insecurity. These emotions compel us to do more of what makes our community value us and less of what doesn’t. And, crucially, they are meant to make that motivation feel like it is coming from within. If we realized, on a conscious level, that we were responding to social pressure, our performance might come off as grudging or cynical, making it less persuasive.

p30

But by 2020, even Twitter’s co-founder and then-CEO, Jack Dorsey, conceded he had come to doubt the thinking that had led to the Like button, and especially “that button having a number associated with it.” Though he would not commit to rolling back the feature, he acknowledged that it had created “an incentive that can be dangerous.”

In fact, the incentive is so powerful that it even shows up on brain scans. When we receive a Like, neural activity flares in a part of the brain called the nucleus accumbens: the region that activates dopamine. Subjects with smaller nucleus accumbens—a trait associated with addictive tendencies—use Facebook for longer stretches. And when heavy Facebook users get a Like, that gray matter displays more activity than in lighter users, as in gambling addicts who’ve been conditioned to exalt in every pull of the lever. See Chapters 6+7

Pearlman, the Facebooker who’d helped launch the Like button, discovered this after quitting Silicon Valley, in 2011, to draw comics. She promoted her work, of course, on Facebook. At first, her comics did well. They portrayed uplifting themes related to gratitude and compassion,

p31

which Facebook’s systems boosted in the early 2010s. Until, around 2015, Facebook retooled its systems to disfavor curiosity-grabbing “clickbait,” which had the secondary effect of removing the artificial boost the platform had once given her warmly emotive content.

“When Facebook changed their algorithm, my likes dropped off and it felt like I wasn’t getting enough oxygen,” Pearlman later told Vice News. “So even if I could blame it on the algorithm, something inside me was like, ‘They don’t like me, I’m not good enough.’” Her own former employer had turned her brain’s nucleus accumbens against her, creating an internal drive for likes so powerful that it overrode her better judgment. Then, like Skinner toying with a research subject, it simply turned the rewards off. “Suddenly I was buying ads, just to get that attention back,” she admitted.

For most of us, the process is subtler. Instead of buying Facebook ads, we modify our day-to-day posts and comments to keep the dopamine coming, usually without realizing we have done it. This is the real “social-validation feedback loop,” as Sean Parker called it: unconsciously chasing the approval of an automated system designed to turn our needs against us.

p32

To understand identity’s power, start by asking yourself: What words best describe my own? Your nationality, race, or religion may come to mind. Maybe your city, profession, or gender. Our sense of self derives largely from our membership in groups. But this compulsion—its origins, its effects on our minds and actions—“remains a deep mystery to the social psychologist,” Henri Tajfel wrote in 1979, when he set out to resolve it.

Tajfel had learned the power of group identity firsthand. In 1939, Germany occupied his home country, Poland, while he was studying in Paris. Jewish and fearful for his family, he posed as French so as to join the French army. He kept up the ruse when he was captured by German soldiers. After the war, realizing his family had been wiped out, he became legally French, then British. These identities were mere social constructs—how else could he change them out like suits pulled from a closet? Yet they had the power to compel murderousness or mercy in others around him, driving an entire continent to self-destruction.

The questions this raised haunted and fascinated Tajfel. He and several peers launched the study of this phenomenon, which they termed social identity theory. They traced its origins back to a formative challenge of early human existence. Many primates live in cliques. Humans, in contrast, arose in large collectives, where family kinship was not enough to bind mostly unrelated group members. The dilemma was that the group could not survive without each member contributing to the whole, and no one individual, in turn, could survive without support from the group.

Social identity, Tajfel demonstrated, is how we bond ourselves to the group and they to us. See Chapters 6+7. It’s why we feel compelled to hang a flag in front of our house, don an almamater T-shirt, slap a bumper sticker on our car. It tells the group that we value our affiliation as an extension of ourselves and can therefore be trusted to serve its common good.

During lunch breaks on the set of the 1968 movie Planet of the Apes, for instance, extras spontaneously separated into tables according to whether they played chimpanzees or gorillas. For years afterward, Charlton Heston, the film’s star, recounted the “instinctive segregation” as “quite spooky.” When the sequel

filmed, a different set of extras repeated the behavior exactly.

Chapter 31, Artificial Intelligence and Polarization, continued....